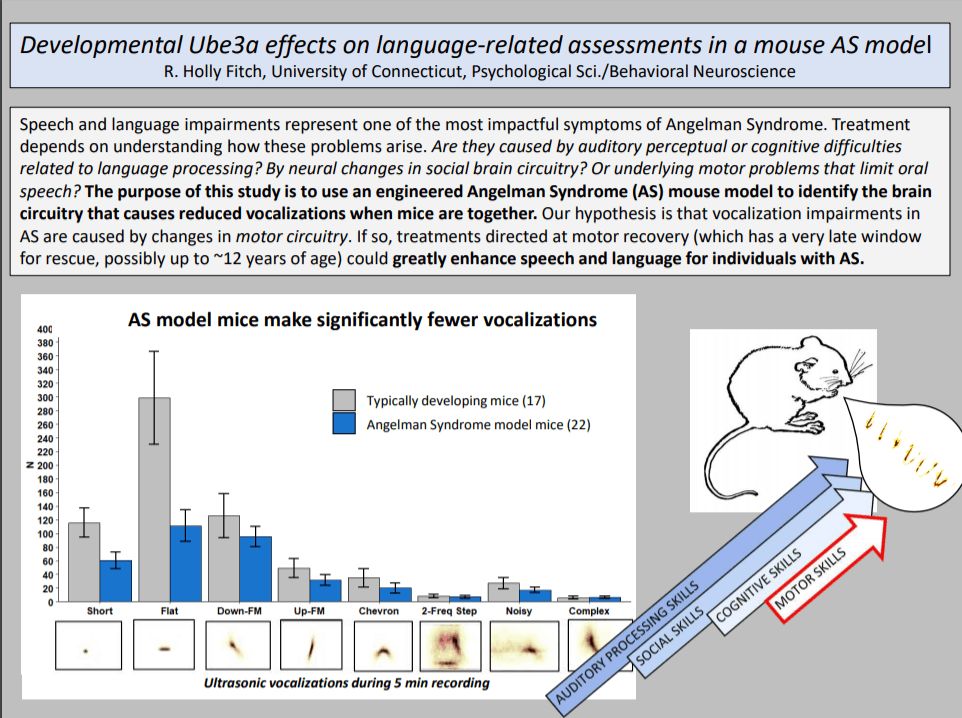

R. Holly Fitch, Ph.D. University of Connecticut

R. Holly Fitch, Ph.D. University of Connecticut Developmental Ube3a effects on language-related assessments in a mouse AS model

Dr. Fitch’s lab has found that the Angelman syndrome mouse model has fewer vocalizations (communication) than typically developing mice. This project proposes to find the brain circuitry responsible for the reduced communication in mice. Preliminary studies suggest it is probably motor circuitry that is most important for vocalizations in the AS mouse model.

This work will help us better understand the brain regions involved in speech and language disorders for AS, which will provide insight as to the therapeutic window for treating communication difficulties in AS.

Why is this study important?

We would all love to see individuals with AS be able to communicate their needs using words. This research project set out to understand whether the lack of verbal communication in AS was due to difficulty in social interaction, “thinking” of words, or the motor skills needed to form words with the mouth. They found that the motor skills to form words are most likely the biggest reason mice with AS do not communicate like their typical counterparts. This is important to help understand the brain region (see also Dr. Hantman’s work) and processes needed for language development.

Results

The major findings were:

- Angelman mice have slightly enhanced (better!) receptive auditory processing ability

- Angelman mice have reduced vocalizations

- The reduced vocalization was strongly correlated with motor deficits and not deficits in social interactions or auditory processing, unlike what is seen in mouse models of autism.

This means that the Angelman mouse model can be used to study communication deficits and that motor impairments contribute heavily to the communication deficits in Angelman syndrome.

Results demonstrate that mice lacking the Ube3a protein show behavioral changes very similar to those in children and adults with Angelman syndrome (AS). The AS-model mice showed gross and oral-specific motor deficits, reduced anxiety with heightened exploration, enhanced social interest in other mice, and learning and memory delays (although these disappear with enough experience).

Of particular interest was the significant delays in development and reduced expression of vocal communications in AS-model mice. (These are the high-frequency “calls” mice use to vocally communicate with each other). AS-model pups are delayed in producing communicative calls, and adult AS-model mice make fewer of them — despite being very friendly with other mice.

Researchers used statistics to show that there is a strong and direct relationship between oral-motor impairments in AS model mice, and the reductions in their communicative vocal output. In other words, mice with particular difficulty in oral-motor tasks are also the ones who made the fewest calls. This is important, because it suggests problems with communication in Angelman syndrome may not be the result of social issues, or cognitive or learning impairments. Rather, the verbal expressive problems in AS may have very much to do with the ability to control the oral musculature. This is clinically important, because motor difficulties may be particularly amenable to therapeutic treatment, meaning that communication (verbal expressive) problems may also be amenable to later therapeutic interventions in patients and families dealing with AS.